It’s that time again. We get to pick a new president. And what an array of choices: socialists, secretaries, surgeons and senators, as well as several governors, a Clinton, and of course Donald Trump, who has excited the electorate and insulted most of the world’s mainstream religions. Is this a great country or what?

From Single Payer to Repeal and Replace

The range of political options is staggering and extreme. Bernie Sanders has unapologetically advocated for a single payer system, which is energizing college students (but not so much members of the U.S. Congress).

At the other extreme, Ted Cruz has sworn to repeal and replace Obamacare and end employment-based health insurance. And Ben Carson would like everyone to have a lifetime health savings account.

With the exception of Hillary Clinton, who has vowed to build on Obamacare and expand coverage and affordability (which is code for more subsidies), all of the candidates’ positions would limit the growth in dollars flowing into health care. And less money in the future will mean fewer health care jobs created.

As the national domestic policy debate centers on profound policy disagreements over jobs, income inequality and health care policy, let us not lose sight of the fact that health care is a major jobs engine delivering good jobs at good wages.

A Resilient Jobs Creator

I was always taught that health care expenditures equal health care incomes. It is a perfect equation. Expenditures are a function of the number and type of services delivered multiplied by the price. And the total expended on health care exactly equals the number and type of people employed in the health care system multiplied by their income. (OK, there is a little leakage to insurance and profit, and to drugs and supplies and so forth. But insurers and pharmaceuticals hire people, too, to misquote Mitt Romney.)

Let’s be clear. Spending more on health care has an opportunity cost. We could spend it perhaps more productively (and in more health producing ways) on education, housing, transportation, infrastructure and so forth. But that is not likely. Instead, in a world where globalization and technology and the ravages of the financial crisis have gutted the finances of the middle class, health care remains a resilient middle class jobs creator. Health care really is the mother of all Keynesian industries, and more productive and humane than digging holes and filling them up again (which is what Keynes once advocated because of the effect on employment and income).

But what are the facts? How good a job creator is health care?

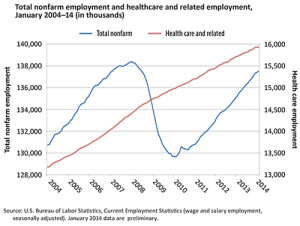

The Chart

The chart below was published in 2014 in a major review of health care and employment by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). It shows the

resilience of health care employment through the dramatic job losses of the Great Recession.

From 2004 to 2014, health care added approximately 250,000 jobs per year. And since the report was published in 2014, we have seen the coverage expansion of Obamacare kick in. Jobs in health care have grown in parallel at an annualized rate of 400,000 to 500,000 per year over the last two years.

This is not new. A September 2007 BusinessWeek cover showed a Rosie the Riveter look-alike in nurse’s garb. The story detailed that basically all of net private sector job growth from 2000 to 2007 was found in the health care sector.

(Critics of the article at the time pointed out that other sectors of the economy, like retailing and food services, also added jobs on a net basis. But these sectors were swamped by manufacturing job losses, leaving health care as the industry accounting for all the overall net growth in jobs.)

Any way you cut it, health care is a major jobs creator and consistently has been for decades.

And for most geographic areas, from rural America to the largest cities, health care is a major if not the major employer. In a lot of America, health care is a key element of the economic base.

Growth in Good Jobs at Good Wages

The BLS report from 2014 not only looked back but ahead at the prospect for jobs growth in health care. The BLS forecast 26 percent growth in health care employment from 2012 to 2022, an increase of about 4.1 million jobs over the period. Growth in employment in offices of health practitioners accounted for 1.2 million of that overall growth, with hospitals accounting for approximately 800,000 of the increase — the balance (a 2.1 million increase) being in home care, long-term care and other ambulatory services. Indeed, home health care is forecast to experience the most growth in jobs of any sector by a full 60 percent from 2012 to 2022.

And these are good jobs. Most of the growth in hospital jobs is expected to occur in occupations such as nursing or hospital administration, with incomes in excess of $60,000. In the ambulatory environment and alternate site environment, more of the jobs are in occupations such as aides, assistants and personal care staff, although jobs for nurses are forecast to grow substantially in these sectors, too.

And many of these jobs are unionized, with resulting higher incomes. While unionization continues to decline across all industry sectors (with only 6 percent of the private sector labor force in unions), health care has a higher penetration of unionization (approximately 11 percent nationally), but not nearly as high as public sector employees (where over

a third of the workforce is unionized).

Why will health care jobs continue to grow? According to the BLS, the basic drivers are demographic: A growing, aging, more chronically ill population provides the fuel for health care demand. Add the technological advances that will create new procedures, tools and interventions along with the coverage expansion of recent years, and it seems hard to believe that growth will somehow stop.

The demographic factors are certainly important key driving forces for employment growth. And there is reason to suspect that employment growth will come from the stunning and increasing complexity of health care. Think: navigators, Medicaid eligibility workers, population health managers, care management professionals and social media specialists, to name a few.

Could the Jobs Engine Stall?

If Ted Cruz or Bernie Sanders were to prevail and have his ideas actually implemented, then we are probably looking at significant reductions in health care employment. Economists have reviewed Bernie Sanders’s plans and, at best, they estimate the Sanders plan would reduce health expenditures by a half trillion dollars or so (which, remember, equates approximately to a half trillion of jobs and incomes).

If more moderate regulatory schemes were implemented — for example, the proposals academic researchers

have made to limit all private insurance payment rates to no more than 125 percent of Medicare — such schemes would likely require a minimum of 20 percent layoffs in hospitals, given current care models.

Donald Trump will take care of everyone with health care and will bring so many jobs back that we will have plenty of good jobs in every industry … for the best people. So maybe we don’t have to worry about health care jobs in a Trump administration. I relish reviewing the specifics.

But the jobs engine could stall for reasons beyond political and policy malfeasance. Here are some trends to watch for:

Care redesign. If we seriously move from volume- to value-based payment and redesign care, we may change the locus of care even more dramatically than is already forecast by the BLS report. Creative use of scope of practice changes, new technology and innovative care pathways could transform the jobs outlook.

Uberization. Uber is a metaphor for disruptive innovation. Uber has killed taxis in many cities and now threatens to enslave debt-ridden Uber X drivers who have company car loans and need to keep driving to pay them off. Kinda like cab drivers, eh? We have yet to see a big disruptive player in health care. But if it comes, it could change the jobs outlook. I am not holding my breath. Software solutions don’t change diapers, or give bed baths.

Immune to foreign competition. One key advantage health care has over most industries is that it is harder (but not impossible) to outsource health care to other countries. While there is some medical tourism (of which the United States is still a net beneficiary), health care remains a local good delivered in person. There are obvious exceptions — from Australian-based radiology services to flying to Thailand for a hip replacement. But for most Americans, health care will be delivered and consumed locally, creating good jobs at good wages.

Ian Morrison, Ph.D., is an author, consultant and futurist based in Menlo Park, California. He is also a regular contributor to H&HN Daily and a member of Speakers Express.