As we enter a new political season, the direction health care policy and practice should take will be hotly debated. Do we know if expanded coverage has increased access to care? How affordable is that care, really? And in turn, what impact has increased access to care had on the health of populations? Drawing on a range of evidence from the Oregon Medicaid experiment to the national coverage and access trends under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), this column tees up the debates on “if not Obamacare, then what?” And if we actually do proceed as planned with the ACA and marketplace reform, how do we improve the connection between coverage and health?

The Connection between Coverage and Health

Giving people insurance cards doesn’t mean that you have necessarily improved their access to health care and health. That connection is not lost on health policy leaders. As Peter Lee, executive director of Covered California, told me in an interview: “We are very focused on all parts of the chain connecting affordable insurance coverage to access to care that the insurance provides, and in turn to the performance of the health care system in delivering health for the population we serve.”

It is undeniable that coverage has been expanded substantially under Obamacare, with approximately 20 million of the 50 million uninsured gaining coverage (half through Medicaid and half through exchanges). Coverage expansion has been achieved in every state (except Wyoming), even in states that were strongly opposed to coverage expansion through Medicaid. Indeed, a recent State Scorecard report published by the Commonwealth Fund covering data through 2014 found that 39 states had reductions in the rate of uninsured of 3 percent or more. Ten states had even more major reductions (6 to 9 percent), from around 20 percent uninsured to around 12 percent. These 10 states, including California, Washington and Kentucky, expanded Medicaid and established high-functioning state exchanges.

The Commonwealth Fund report also lays out substantial progress in many states on performance measures such as access to care, equity, affordability, health system performance on such issues as readmissions and preventable harm, and prevention. On balance, it seems that much has been achieved across the country in coverage expansion, access to care and improving health.

But there is also evidence that the promise of Obamacare has not been completely fulfilled in many dimensions, such as true affordable coverage (particularly for ambulatory services), reduction of unnecessary emergency room (ER) visits, access to primary care and specialty care services, and impact on health outcomes.

This wide range of emerging evidence, sometimes contradictory, is being used (and sometimes abused) in political and policy circles as candidates prepare for party primaries and the presidential election debates ahead. What should we make of the progress so far? What matters to hospitals and health systems? And what does it mean for the future?

Following the Chain from Coverage Expansion to Health

The chain between coverage expansion and health starts with affordable coverage, and that affordability has two main components: premium levels and out-of-pocket costs. The cornerstones of the ACA were Medicaid expansion and insurance exchanges. Medicaid is characterized by low cost sharing and premium sharing in most states, although Republican governors and statehouses in states such as Ohio and Indiana have pursued Medicaid expansion using more aggressive cost sharing: skin in the game for poor people. Brilliant.

The core starting point of affordable premiums is a high-functioning risk pool and the rules of the road to maintain it. Covered California’s Lee points to the principles that the California exchange has followed from its inception: “We are an active purchaser state; using standardized benefit designs with fewer simpler, clear and comparable options; and no plan differences in the individual market inside or outside the exchange.”

Rate increases nationally on insurance exchanges for 2016 vary widely, but the basic lesson is that if consumers are prepared to shop around, the rate increases for 2016 can be manageable and modest. Take Nebraska, a typical non-expansion state with moderate numbers of uninsured close to the national average. In Nebraska the approved exchange insurance premium rates increased anywhere from 15 to 30 percent for 2016; however, two new insurers entered the market for 2016, offering rates that were identical if not slightly lower than the market leading rate of 2015. So careful consumers could have zero increase in premium from 2015 to 2016. That is the general story: the more high-functioning the exchange (such as an active purchaser like California), the more competitive the insurance market (not sheer numbers of players but also their capability and commitment to the market) and the more the consumer is prepared to shop around, the more affordable the rate is likely to be. Hey, that’s why the call it a market.

Obamacare critics carp about “corporate welfare for insurers,” referring to the three Rs program (risk corridors, reinsurance and risk adjustment) that are intended to make insurers whole, financially if they suffer extraordinary adverse selection from sick patients. Similarly, United Healthcare recently complained it is losing money on its exchange business nationally and threatened to pull out in 2017. No such concerns exist in California, according to Lee: “Insurers are not losing money in California, and they paid into the national risk corridor program rather than needing a rebate.” Again, here is testimony to a high-functioning risk pool and an active purchaser marketplace.

But elsewhere the picture is not always so rosy. For example, the CO-OPs (local, community-based nonprofit startup health plans created with seed funding from the ACA) were all counting on three R bailouts to make it through the next winter. Not happening. Sorry, CO-OPers, this was a bad idea from the start. I had a slide when CO-OPs first were conceived that showed a grainy picture of an Amish barn raising, onto which I photoshopped a neon sign that said: “North Dakota CO-OP: We suck! But we’re Local.” Weirdly prophetic. This was amateur hour and it should never have happened. Just like we need to shut out the crazies on the right, we need to shut out the crazies on the left; CO-OP is a perfect example of Liberals Gone Wild.

Done correctly, exchanges orchestrate access to private insurance, and most importantly, they are the vehicle for delivering both premium subsidies and cost sharing support. Nearly 90 percent of Americans gaining access to coverage through state and federal exchanges are receiving some form of subsidy. And let’s be clear, many of those folks (some would argue most) would not buy the coverage without a subsidy because they simply could not afford coverage and still eat.

Critics of exchanges (from both the right and the left) have argued that Obamacare is not really affordable coverage even after subsidy because of the high deductibles. It is true that Obamacare has legitimized high deductibles by establishing high thresholds for individuals and families, but compared with what? Employer-sponsored coverage? Surveys show that 40 percent of workers with employer sponsored coverage now have a deductible of $1,000 or more, and 20 percent have a deductible of $2,000 or more (and the proportion of Americans with ever higher deductibles grows every year).

Less attention has been paid to the cost-sharing reduction provisions of the ACA for those covered through exchanges that earn less than 250 percent of the Federal Poverty Level. In California that is 58 percent of all those covered through exchanges (similarly nationally). The cost sharing provisions substantially increase the actuarial value of the plan and therefore reduce the total financial burden for low income folk, and the provisions have significantly reduced the barriers to accessing care.

Awareness of these provisions remains relatively low in the general population and in the populations who would benefit. Yet in surveys of newly covered populations who now understand their coverage, satisfaction with covered benefits and out of pocket costs is as high if not higher than those with employer-sponsored coverage.

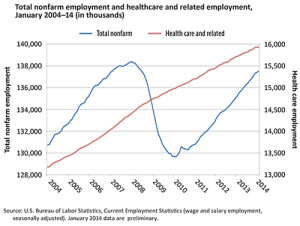

Coverage expansion has

undeniably helped hospitals and health systems by substantially reducing the uncompensated care burden. But the rise of high deductibility has dampened demand for some ambulatory services and has potentially increased bad debt for physicians who are seeing more patients with high deductibles. In addition, Medicaid expansion and exchange related discounts to insurers have weakened margins as payer mix for hospitals and physicians skews more toward public coverage. Overall, coverage expansion has been a financial positive as evidenced by various metrics such as the overall reduction in uncompensated care and the robust economic performance of for-profit hospital providers attributed to the positive effects of coverage expansion.

Access to Care

Getting an insurance card should improve access to health care services, and apparently it has. A March 2015 tracking survey by the Commonwealth Fund, reviewing progress from ACA expansion, found that 68 percent of the newly covered had used the card to access care, and 62 percent of that group said that “prior to getting this coverage, they would not have been able to access and/or afford this care.”

A similar story comes from Kaiser Family Foundation surveys conducted on the California experience and released in May 2015. The report found that among the newly covered, significant majorities had a usual source of care and a regular doctor compared with a minority of the uninsured. In particular, 43 percent of uninsured adults reported a usual source of care, with 22 percent having a regular doctor; among the newly insured, the percentages were 61 percent and 43 percent respectively, compared with 80 percent and 70 percent for the previously insured.

Looking at all Covered California members and all Medicaid members compared with the privately insured, both Medicaid (71 percent) and Covered California members (69 percent) have a usual source of care, which is getting close to the 81 percent rate enjoyed by the privately insured. As these newly insured are gradually absorbed into the delivery system and they “learn” to use their new coverage, these numbers are likely to rise.

As Lee told me succinctly: “We have not been flooded with complaints from people who can’t access doctors.”

The Kaiser Family Foundation study found that only 7 percent of the newly covered Californians had providers say they did not accept their coverage, compared with 4 percent of the previously covered.

But, the access to care issue is complicated. Which providers? What settings? What quality? What about specialists? Do we have enough primary care providers? What

happens in 2016 when payment rates for primary care under Medicaid revert back to previous levels (not the Medicare levels providers have enjoyed for the last two years)?

These are all good and difficult questions to answer easily. Here are some clues:

Where was the massive primary care surge? Despite claims of massive surges in primary care demand that we heard from some physicians and health systems, a study conducted by Athena Health based on data from their 16,000 providers found a surprisingly low increase in visits to primary care practices. This makes intuitive sense to me: As one of my old physician colleagues taught me, “there is only so much doctoring you can do in a day,” and absent a massive increase in supply of primary care physicians, why would we expect capacity and volume to increase massively? Indeed, when Canada finally got universal physician insurance coverage in the 1960s, overall demand for primary care did not increase much. (Higher income folk got fewer visits and lower income folk got relatively more.)

Did all the new demand end up in the ER? Another survey released in 2015 of a large sample of more than 2,000 emergency room physicians found a substantial increase in ER visits that could be attributed to the newly covered, due particularly to Medicaid expansion. In particular, 28 percent said that volumes to their ER had increased greatly since the ACA was implemented, and a further 47 percent saw slight increases. Historically, ER utilization research has shown that as many as third of visits are for conditions that could and should be seen in routine primary care settings, but because of convenience, primary care physician preference or perceived sophistication of services, patients end up in the ER. Emerging benefit designs for employer-sponsored coverage and for exchanges are intended to encourage beneficiaries to seek routine care in less expensive settings than the ER, but it is harder to craft such incentives in the Medicaid population.

What about network adequacy and affordability? “Narrow networks are a necessary building block of affordable coverage,” Covered California’s Lee told me. And while exchange recipients in surveys report less of a preference for broad networks than those in employer-sponsored coverage, the issue becomes significant for new members when they have a serious illness and may find certain providers (particularly high-profile ones) are simply excluded because of the providers’ high costs.

For me, this has gotten personal. In California, products, networks and plans in the individual market are identical inside and outside the exchange. As I have written in these pages before (see “My Journey through Obamacare”), I am in the individual market, and all I need is a low-cost narrow network that includes the Palo Alto Clinic (part of Sutter Health) and Stanford Health. The reason I like both of these systems is partly because they have national and international reputations for quality, but mostly because I live within walking distance, and I am a geography major. As we geographers say, nothing compares with propinquity.

Unfortunately for me, my insurer, Blue Shield, severed its contract with Sutter, and more recently with Stanford, because both are deemed to be excessively expensive. In a spirited letter to Stanford leaders that was widely leaked, Blue Shield’s CEO pointed to Stanford’s prices, margins and profits in comparison with Shields’ self-imposed pledge to return any profits in excess of 2 percent to customers. All noble … but now I have to drive to UC San Francisco if I get really sick.

As far as I can determine, I cannot buy any Blue Shield plan that includes these local providers. I am not sure if any plan marketed to individuals includes them, but finding that out would involve hiring Homeland’s operatives to do the necessary espionage on who is actually in what network.

This little drama is playing out everywhere. Who to blame? Obama, Covered California, Blue Shield, Stanford and Sutter, me, all of the above, no one?

The Last Mile: The Connection to Health

So coverage does seem to help access to care, but does it improve health? We have some answers from the Oregon Medicaid studies.

Oregon presented health services researchers with a rare gift in social science: a randomized trial. In 2008, Oregon wanted to expand Medicaid but had limited resources, so it had to limit expansion to 35,000 of the 85,000 on the proposed eligibility list. The solution: a lottery. Assign them at random. This is as good as it gets for research economists.

Researchers at Harvard, MIT and Oregon Health Sciences University jumped at the opportunity to analyze what effect coverage expansion

really did have, not only on access to care but also on the health and financial outcomes for enrollees. What did they find?

Coverage expanded utilization. Not surprisingly, and consistent with all we have seen with Obamacare, coverage increases utilization. Comparing the covered with the uncovered: Outpatient care was 35 percent higher, hospitalization was 30 percent higher, prescription use was 15 percent higher. And 18 months after implementation, ER visits were up 40 percent. The study found: “Overall, the increased health care use from enrollment in Medicaid translates into about a 25 percent increase in annual health care expenditures.”

Prevention improved. Coverage improved preventive practices, with cholesterol monitoring up 50 percent and mammograms over age 40 doubling, for example.

Beneficiaries were better off, financially. Catastrophic financial consequences of health care were eliminated for the covered population, and the financial burden to enrollees was sharply reduced.

Health improvement proved more elusive. The study found that in the first one to two years of coverage, Medicaid

improved self-reported health and reduced depression, but had no statistically significant effect on several measures of physical health. In particular, the study found that:

“Medicaid increased the probability that people reported themselves in good to excellent health (compared with fair or poor health) by 25 percent.

“We did not detect significant changes in measures of physical health including blood pressure (systolic or diastolic), cholesterol (HDL or total), glycated hemoglobin, or a measure of 10-year cardiovascular risk that combined several of these risk factors. Nor did we detect changes in populations thought to have greater likelihood of changes, such as those with prior diagnoses of high blood pressure of the portion of our population over age 50.

“Rates of depression dropped by 9.2 percentage points, or a 30 percent reduction relative to the control group rate of 30 percent.”

On balance, coverage did have an effect on self-reported health status and on depression, but did not have any measurable effect on objective measures of physical health, which many observers would argue is the ultimate goal of the health care system and of expanding health care coverage.

The Chain of Coverage Expansion to Health and Its Impact on Policy and Politics

Iowa is upon us — and then who knows who will be running the country?

If Republicans are ascendant in 2016, they will seek to chip away at Obamacare and roll back subsidies and Medicaid expansion, jeopardizing the coverage gains made for 20 million Americans. The candidates and their advisors have said as much. Less money for subsidies and more block grants and flexibility will in turn will have a major impact on reducing utilization and revenue for hospitals and health systems that have benefited economically from expanded coverage.

If Democrats prevail, their focus will likely be on expanding coverage to the still uncovered; minimizing the economic damage of cost sharing to all who have coverage, including those with employer-sponsored coverage; and minimizing the economic damage that consumers face from high-priced outliers. A good example of what may lie ahead is the No Surprises Law in New York, where providers have to give the consumer a heads up in advance that they are going to be screwed by the second assistant surgeon who is out of network. Nice try, but it doesn’t really solve the problem. If Democrats prevail, hospitals and health plans will feel pressures on margins from attempts to box them in on price, either directly through regulated prices or indirectly through requirements on network adequacy and standardization of benefit design.

So pick your political poison: pressure on the top line or the bottom line. Depending on your mission, vision and values, you’ll make it all work one way or another. That’s your job, and I have confidence in you all.

Implications for Hospitals

No matter who is running the country, hospitals can learn from what we know about the connection between coverage, affordable care and health outcomes. And we should use these insights to encourage us to find new ways to deliver care that are more affordable to cover and are more effective in outcome. In particular:

Don’t expect massive expansion in coverage. Even if Democrats prevail, don’t expect massive coverage expansion from 2015 levels. Exchanges will do well to have the same number of enrollees who have paid their premium by the spring, as they did at the end of 2015. Why? Overcoming the 30 percent churn is an enormous head wind, given that the low-hanging fruit have signed up and an improving economy has meant that employer-sponsored coverage has remained stronger than expected in a tightening labor market. Further Medicaid expansion is possible in some states, but many of the more conservative state legislatures will still resist Medicaid expansion like they resist Syrian refugees (even if Hillary is president).

Ask whether medical care is just overrated. I must confess I find it a bit of a buzz kill to find the whole connection of coverage expansion to health outcomes falls apart at the end of the story with the results from the Oregon Medicaid experiment. Is medical care just over-rated as a contributor to human health? Is it just so for low-income people? Do we have the right delivery models to truly connect the dots? I think we have to use this as a learning opportunity to rigorously explore models of care delivery that improve outcomes, not just provide access to medical services.

Focus on delivery model innovation for Medicaid and low-income populations. A specific subset of this problem is finding sustainable, affordable and effective delivery models for low-income, economically vulnerable enrollees in Medicaid and beyond (even in employer-sponsored coverage). High-deductible narrow-network insurance is not a coverage panacea for the bottom half of the income distribution, no matter who pays for their coverage, nor perhaps is episodic fee for service delivery. But what? Kaiser may help us find solutions as it takes on more Medicaid patients, and other health systems are exploring targeted delivery innovations focused on lower income patient segments. We need more solutions, including new delivery models. FQHC 2.0 perhaps?

Be accountable for health outcomes. In all our dalliances with accountable care, we must remember to be accountable for health, not just ticking all the boxes of service delivery. As the Commonwealth Fund state scorecard shows, we are making significant progress on all fronts across the entire country. Let’s build on that progress and better connect the dots from coverage expansion to health creation. And most of all, please let’s not get distracted by political demonization and demagoguery that undermines or reverses the substantial gains we have made and the significant improvement that will lie ahead if we are smart and focused on our important work.

Ian Morrison, Ph.D., is an author, consultant and futurist based in Menlo Park, Calif. He is also a regular contributor to H&HN Daily and a member of Speakers Express.